Anxiety Part Two: Anxious Like Me

“Oh your “brain” is acting “illogically”? It’s meat with electricity inside, what the f*ck did you expect”

~Twitter user @KylePlantEmoji

IV

To the best of my understanding, theories of emotion are attempts to answer the question, “WHAT IS THIS FEELING, WHY DO I HAVE IT, AND WHAT’S WITH THIS SALTY DISCHARGE COMING FROM MY EYES?” Thankfully, we’ve mostly outgrown humour theory, so relatively few people still say you’re depressed due to an excess of black bile. But then again, within the last month, I heard people attribute feeling states to another ancient theory of medicine. So, while the numbers have become fewer, they’re still nonzero.

One way to explain emotions is to look at the systems that are involved when emotions arise. A number of theories have arisen that divide along the lines of whether emotions should be viewed as governed primarily by physiological (James-Lange Theory), neurological (Canon-Bard Theory), or cognitive (Appraisal Theory of emotion) systems. These different theories emphasize, respectively, that emotion is primarily a phenomenon of the body, the brain, or the mind. There’s clearly a role each plays, but there is division between the theories with regards to what we ought to consider the primary phenomenon which we call “emotion.”

In his lectures on human behavioral biology, American neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky gives us a perspective on the cascade of processes that underlie emotion:

“It’s not the case that your brain decides it’s feeling an emotion based on sensory information coming in, memory or whatever. It’s not that the brain decides it’s feeling an emotion and tells the body let’s speed up the heart, let’s breathe faster, let’s sweat, or whatever it is. That’s not how emotion works. Here’s how emotion works: stimulus comes into your brain and before you consciously process it, your body is already responding - your heart rate, your blood pressure, your pupillary contractions, whatever.

How do you figure out what emotion you’re feeling? You get information back from the periphery telling you what’s going on down there. In other words, how do you figure out you’re excited? Whoa! If I’m suddenly breathing real fast and my heart’s beating fast, it must be because I feel excited now.

Ridiculous. Totally absurd way in which you process stuff. Completely inefficient. And, over the years, after decades of being wildly discredited, more and more evidence that is some of how emotion is based: your brain being influenced by your bodily state to decide which emotions it’s feeling.” (from Sapoksly’s lecture on the Limbic System)

Sapolsky is great for his ability to engage with the ridiculousness of the systems evolution provided us with. You can tell he sees the humor in the humanity of it all. He expresses incredulity at the body of evidence which suggests that we experience emotions in a roundabout way: brain systems well outside of our consciousness respond to stimuli, changing the physiological state of the body... then brain systems partially within our consciousness feel what the body is doing and get around to naming that feeling. In his whimsical style, Sapolsky is throwing his hat in with something like physiological-neurological theories of emotion.

V

To truly understand emotion, we need to spend time understanding each of the different aspects outlined in the previous section. Emotion is a physiological, neurological, and a cognitive phenomenon. So while Sapolsky gives credence to something like a physiological-neurological theory of emotion, in this section I’m going to look at why we might give credence to cognitive theories of emotion.

Sapolsky said we eventually get around to naming the feeling. But what is that process? Naming the feeling is the process that American psychologist Richard Lazarus emphasizes. Lazarus was one of the progenitors for cognitive theories of emotion and, more specifically, cognitive appraisal theory of emotion.

His work took off in the 60s and helped bring American psychology out of the limited examination of behavior and into the study of cognition. Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion emphasizes the role of our mind’s capacity to place physiological sensations into context to assess what’s going on.

In Emotion and Adaptation, Lazarus connects emotions to reflexes and drives. Reflexes, drives, and emotions are responses that help us meet our needs in our environment. But they differ in the rigidity of their response. Reflexes, like startling or blinking, are largely involuntary fixed patterns of action — the response is basically the same each time. Drives like hunger and thirst motivate predictable classes of behavior, but the particulars of the response can vary. Emotions, like anger or anxiety, allow for much greater flexibility in response.

Emotions arise subsequent to stimuli. The stimulus can be internal or external, real or imagined. But the stimuli that give rise to emotions are related to each other in that they signal something significant for well-being may be at stake. The brain quickly interprets the stimulus and assesses whether it is salient for survival. If the stimulus is assessed to be salient for survival, this leads to a complex reaction of the body and mind which fuses thought, motivation, impulse, and physiological changes. Our reactions are processes that occur in the brain and body, which can be schematic or conceptual. Schematic processing is passive and automatic. Conceptual processing is conscious and deliberate.

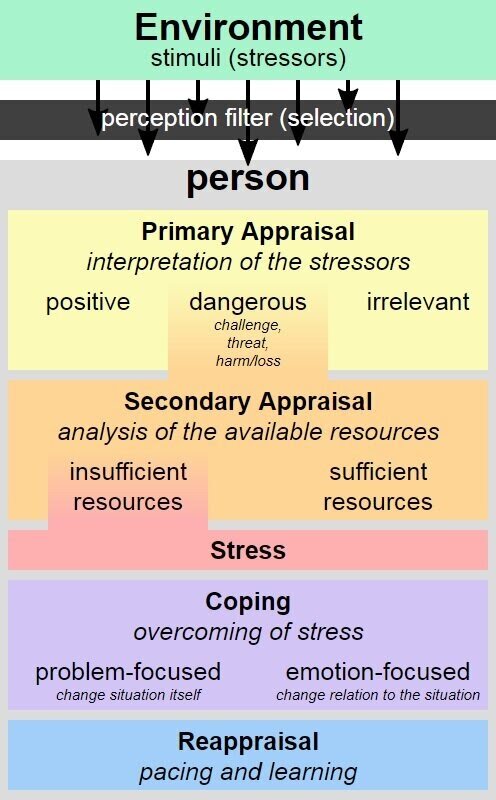

I was interested in what Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion has to say about anxiety, and thankfully Wikipedia has a colorful model of Richard Lazarus’ Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, which may help illustrate how we worry:

Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion regards each emotion as having a “core relational theme” of the individual relating to the situation. Anxiety’s core relational theme is interpreting ambiguous dangers or uncertain threats in the situation.

The graph above illustrates the process that leads to the emotion arising. Stimuli is perceived. That sense data is modeled in the mind in the primary appraisal process where we generate knowledge/belief about the situation and assess whether the situation is positive, irrelevant, or dangerous. We then assess whether we have the right resources to maintain personal well-being in the situation. If it is determined that resources are not present, it contributes to the anxious theme of uncertainty. Coincident with these negative assessments, the emotion of anxiety is produced. We feel the stressful emotion and begin to seek out ways to overcome anxiety by either managing the problem or the internal emotional process.

In Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, this subjective interpretation of stimuli is affected by biology, personality, and culture. Because emotions arise out of our interpretation or evaluation of a stimulus, emotion has moved from a concrete event to an abstract meaning. Since we’re responding to an evolving interpretation called meaning, our emotional response is dynamic and tracks the changes in the environment for their significance to our well-being but also tracks the changes in our thoughts and beliefs which assess the situation.

Assessments are flexible and subjective. I interpret things like sweating and elevated heart rate differently depending on the situation. If I’m watching sports, it’s excitement; If I’m exercising, it’s exertion; and if I’m in a meeting, it’s anxiety. This interpretation is not within our momentary volitional control. But in his cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, Lazarus has identified that we can intervene in the process of emotional response through something we might generally call “coping.” We learn to cope with different stimuli, and this coping mediates our emotional response. Just as we can change our habits and beliefs over time, we can adjust our emotional responses.

We all experience growth in our ability to cope internally. Growing out of childhood, we stop interpreting small hungers or pains as crises and rarely respond with the same anguished tearfulness. Learning to swim, we stop experiencing fear and panic at the sensation of water on our faces. Albeit, we may still panic at the feeling of water on our face if it’s thrown during a dinner party.

Lazarus’ cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, falls in between seeing emotions as innate, fixed products of our biological heritage, and sociocultural, following scripts that vary widely across cultures. That is, it does not ignore the physiological and neurological aspects even while giving primacy to the cognitive aspect. This cognitive theory of emotion connects emotions to the biological processes of drives and reflexes, highlighting that emotions come with predictable autonomic, hormonal, and facial expressions. But it also allows room for personality factors that arise in diverse cultural settings.

While not all thought is volitional, our ability to respond to our thoughts is well within our voluntary control. Part of what is compelling about cognitive theories of emotion is how they give us a place to intervene in stress: in the way we interpret our relation to the situation.

While Lazarus’ theory is all well and good and seems to check out with my own internal experience… so does Sapolsky’s description of emotions. I can imagine each of these theories of emotion being true despite them contradicting each other regarding what phenomenon is primary in emotion.

Maybe there’s something I’m missing. I’m tempted to settle this with an appeal to data from experiments — it’s certainly possible that recent experiments have been resolving the disputes between these different theories of emotion. However, it’s really hard to have objective experiments determine something about such a subjective phenomenon.

Incredible experiments based on objective data are what have allowed us to make advances in neuroscience… just look at the debate over free will! Those who discuss this other subjective phenomenon commonly make reference to the study where the awareness of deciding on a choice occurred at a distinctly later time than the unconscious neural activity which initiated acting on the choice. Sapolsky makes reference to similar research in his discussion on feelings above… but even his statement doesn’t completely rule out that cognition could be primary in emotion.

What’s funny about this topic is the extreme epistemic uncertainty we have about it. These theories contradict each other regarding what feelings primarily are. And those disagreements seem to be in part occurring because we don’t really understand what consciousness is — which is ridiculous because it’s literally all that we can possibly be aware of. Am I barking up the tree of the hard problem of consciousness? It sure seems we know a lot more about the thing-in-itself rather than the phenomenal experience of the thing.

I’M A THERAPIST WHO WANTS ANSWERS, DAMMIT! I REQUIRE MORE OBJECTIVITY ABOUT SUBJECTIVITY!

I’m the kind of person to struggle against epistemic uncertainty so I’m not giving up on the topic of what emotions are or the project of digging into everything I can to understand anxiety. In the next post, I’ll wade back into this swamp and brave the miasma as I try to discuss the neurological underpinnings of emotion, honing in on the processes within the brain which produce the experiences we call emotions. I’ll attempt to do justice to the findings of neuroscientists like Damasio and Friston. Make sure to follow my blog to read the next installment.