Interview with Reid Nicewonder, the Cordially Curious Street Epistemologist

There’s a contradiction that sometimes occurs when someone comes into therapy. A client will sit down and express certainty about their inadequacy, badness, and helplessness yet they are entering a space expecting to change. They experience the ambivalence between feeling the belief in their badness, inadequacy, and helplessness is true and expecting that it can be shown to be not true. These beliefs deeply affect their wellbeing and their moment-to-moment suffering makes them profoundly aware of it. Their experience of their beliefs matters.

People voluntarily enter a space in therapy expecting to change. But how do beliefs change? Maybe to know that we need to explore a more fundamental question: How do we know what we claim to know?

A few years ago I became very invested in these questions. I discovered that asking the question, “how do you know?” can be a powerful tool. It seemed so fundamental and important I wondered why I had never had a required course in school that focused on this question. Courses do exist on the subject, though. This simple question is central to a branch of philosophy called Epistemology.

Epistemology deals with belief, justification, truth, and knowledge. The nature of what it’s exploring is so basic to human existence, it’s important it not remain confined to ivory towers of academia. Socrates frequented and used the language of the marketplace, bringing his ideas to the people and “corrupting” the Athenian youth.

I’m glad that there are some communities that continue the Socratic tradition. In 2019, I found one of these communities after YouTube recommended videos tagged with Street Epistemology. Someone with a GoPro would ask if he could film the people who approached as they speak about one of their convictions. And in these videos, the person who approached usually seemed to struggle to answer gently posed, deceptively simple questions.

Rather than running into reason, these conversations quickly ran into psychology as people became defensive, flustered, or rationalized something they hadn’t previously thought about. But the Street Epistemologist filming acted like a therapist, staying gentle and calm during these charged conversations.

I sought out more information about the community, talked to some people who did Street Epistemology, which they just called “SE.” They claimed to primarily be interested not in what people believe, but in having conversations that help people reflect on how they come to believe. To have these conversations, they were developing toolkits of managing a relationship built on conversation which focused on growth and change, which meant they were trying to independently develop the skills that therapists go to school to cultivate.

I’m glad to have gotten to know one of these Street Epistemologists who is deeply invested in the community. Reid Nicewonder is the host of the YouTube channel, Cordial Curiosity. Many weekends, you can find him in Runyon Canyon or Echo Park sitting at a table and inviting people to sit down to talk about what they believe and how they think. He was kind enough to take the time to answer my questions on SE.

Below, my questions are in bold with Reid’s responses following.

EA: What is Street Epistemology?

RN: Street Epistemology (SE) is a positive and productive way to help someone reflect on their reasons and motivations for believing something. Its core structure uses the Socratic Method. There are two roles in the conversation – the questioner (SEer) and the person being questioned (interlocutor / IL). Unlike Socrates, whose style and demeanor was like a gadfly, SE focuses heavily on building and maintaining positive rapport. It uses research from applied epistemology, hostage and professional negotiations, cult exiting, and psychology.

The basic steps of Street Epistemology

A successful SE conversation is when you get to at least one of the blue steps (5 – 7) where you’re exploring the quality of someone’s epistemology while at the same time maintaining the positive rapport you’ve built in step 1 all the way through to the end of your conversation.

How did you get into it?

I originally heard about SE in 2013 after listening to an interview with Peter Boghossian on a podcast. He talked about a different way of having conversations with people about their religious beliefs, one that was potentially much more effective at inspiring reflection. At the time, I wanted to help people think more critically about religion, so I read his book and his advice seemed promising.

It wasn’t until a year later when I came across Anthony Magnabosco on YouTube, who had been uploading examples of SE conversations he was having with the public in San Antonio, that I really got into SE. In contrast to the usual debates I was watching on YouTube, which were hostile and argumentative, Anthony’s conversations seemed calm and effective at helping people reflect on why they believed what they believed. His first videos were a bit rough, but he would post them in the SE Facebook group to get feedback, which he would apply in future conversations.

By 2015, more and more people were uploading their own videos to YouTube. Then a new video chat site called Blab was launched and a bunch of people from the SE community went over there to practice.

Blab allowed anyone to create a public video chat room with up to four people and a chat on the side. So for about a year, myself and many others from the SE community practiced there regularly. When Blab shut down in mid 2016 I was in need of a new place to practice SE.

While I didn’t feel ready to go out and record the way Anthony and many others were doing, reading The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck by Mark Manson inspired me to try to fail-forward. So, one day in the fall, I went to Griffith Park park with a table, two chairs, a mic, a GoPro and started doing public SE interviews.

Reid’s first Street Epistemology setup in Griffith Park

I’m now President of a non-profit dedicated to educating the public about Street Epistemology, supporting the SE community, and obtaining scientific research about its effectiveness.

What are the goals Street Epistemology can help us accomplish? Is SE different from persuasion?

The main goals SE can help us accomplish are giving ourselves an opportunity to understand the reasons that lead someone to confidence in a belief in order to collaboratively reflect on the quality of those reasons. Helping myself and others reason better is my ultimate goal.

A scale Reid uses for indicating confidence in a particular belief

The usual way people try to persuade is through debate, where someone throws out many facts and arguments hoping the other person will change their mind. While SE can be used to persuade, and wanting to change someone’s confidence may often be a goal, it’s rarely the highest priority goal. With SE, we use discussions about beliefs as a means to explore the quality of someone’s epistemology for the end of helping us all become better critical thinkers. If our general methods of reasoning are good, then the calibration of our confidence level in particular beliefs should take care of themselves.

How do people commonly form and change beliefs?

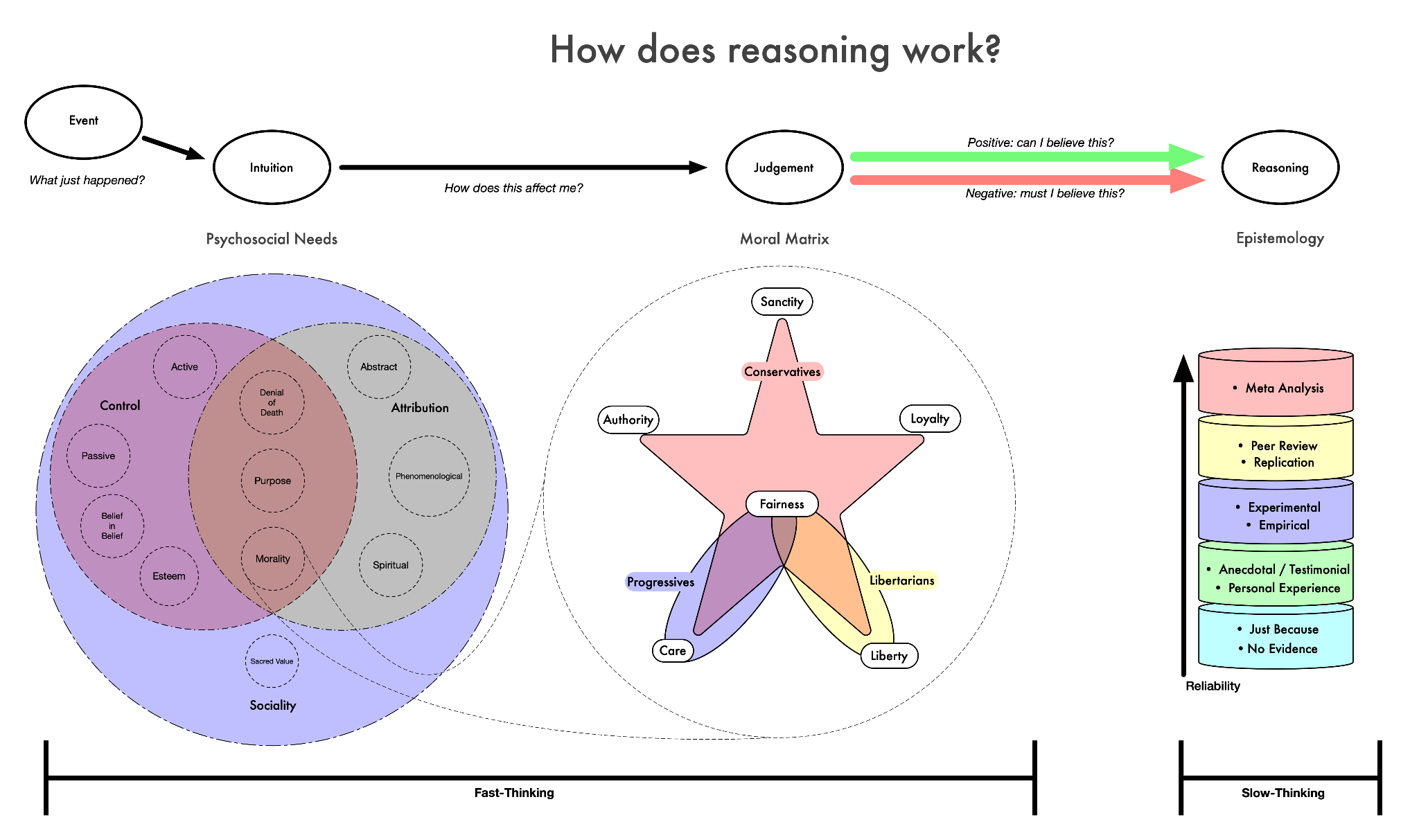

Here is a graphic I’ve been working on to help me make sense of how people’s beliefs work.

Reid’s chart on How Reasoning Works

“Intuition comes first, strategic reasoning second.”

– Jonathan Haidt,

A belief is a feeling of confidence produced by the brain about a concept. When someone encounters a new concept, it passes through a set of unconscious psychological filters, which produces either a negative or positive judgement about the concept. Frequently, reason is only used to support the judgement after the fact, like a press secretary.

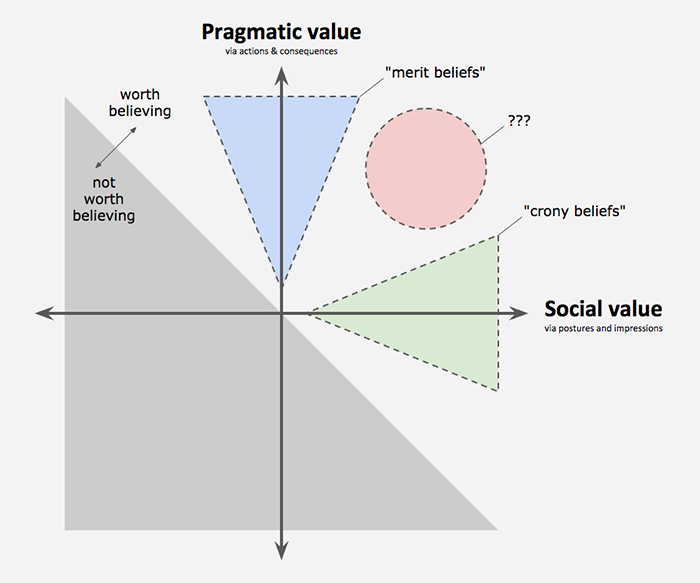

“For our beliefs to function as loyalty signals, we can’t simply “follow the facts” and “listen to reason.” Instead, we have to believe things that are beyond reason, things that other, less-loyal people wouldn’t believe.”

– Kevin Simler & Robin Hanson, The Elephant in the Brain

The most common ways we develop and change their beliefs are related to tribalism. Humans are a hyper-social species. We adopt beliefs from people around us who we respect and admire. While beliefs can allow us to navigate reality pragmatically, acting and making choices to further our goals, this is not usually how we form our beliefs. More often, we form beliefs due to social status. This is because beliefs can be a way of blending in, showing off, or cheerleading the sacred values of our tribe to show belonging.

Crony Beliefs by Kevin Simler

How has Street Epistemology helped you understand how people form and change their beliefs?

I started recording interviews at Griffith Park in September of 2016. At that time I was working with the assumption that most people could be relied upon to change their minds in light of discovering their reasons were either fallacious or poorly justified. This did not happen. People left my table with the same level of confidence they sat down with. This made me want to understand what was going on.

I read Everybody Is Wrong about God in early 2016 where I learned about the psychology of religion including the concept of psychosocial needs. Then I read The Righteous Mind in January of 2017 which included the social intuitionist model and moral foundations theory. In January of 2018, I read The Elephant in the Brain which included signalling theory. Understanding the hidden motivations as to why people practice religion, engage in politics, and have conversations in general made my failures conducting SE up to that point make so much more sense. I now recognize the importance of tribalism, morality, and signalling in relation to how and why people come to their beliefs.

Once I started practicing SE with all of these psychological models in mind, my conversations became much more productive. For example, if I hit a roadblock at the level of reason and evidence, I would go deeper and start to ask probing questions to try and discover how the belief provided a way to meet one of my IL’s psychosocial needs. Once we identified a psychosocial need, I’d help them brainstorm alternative ways to meet it. This allowed my IL to feel more safe and open to talk about the belief and their epistemology and much more genuine reflection occurred.

What is the difference between good and bad epistemology?

“A wise man proportions his belief to the evidence.”

– David Hume

Good epistemology helps us have a reasonable level of confidence about any claim. If our confidence is too high or too low, we’ve used a bad epistemology.

There is a particular set of rules that are reliable at producing reasonable confidence levels with the least amount of conflict. “We have to draw conclusions in life... but we must all take seriously the idea that any and all of us might, at any time, be wrong.” That is to say, we are all fallible. “If you are not inclined to doubt, you never even reach skepticism—it is simply not an issue; you simply believe without asking questions.” Deciding to have this attitude leads to two rules we should follow:

“No one gets the final say: you may claim that a statement is established as knowledge only if it can be debunked, in principle, and only insofar as it withstands attempts to debunk it.”

“No one has personal authority: you may claim that a statement has been established as knowledge only insofar as the method used to check it gives the same result regardless of the identity of the checker, and regardless of the source of the statement.”

This is what Jonathan Rauch in Kindly Inquisitors calls the game of liberal science. If an epistemology violates these rules, it’s a bad epistemology.

In Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, we often discuss adaptive versus maladaptive beliefs where this is referring to whether beliefs are helping people achieve their goals and live a life worth living. Do you think that this is a valid way to talk about beliefs?

I do. Fitness is not the same thing as truth but they’re highly correlated. The more accurate a map we have of the small pocket of reality we’re in, the better we can navigate it. But sometimes truth and fitness conflict. For example, if I’m around a gun that I know is unloaded, the value of the belief, “all guns are always loaded,” influences my behavior around guns in general, even though I’m virtually certain this particular gun is harmless.

There’s a distinction between epistemic rationality and instrumental rationality. Epistemic rationality is about having an accurate map whereas instrumental rationality is about knowing how best to navigate the map in accordance with your goals and values. If my confidence is more than the actual probability that the gun is loaded, then that belief would be instrumentally rational but epistemically irrational.

How are our beliefs related to our wellbeing?

Our beliefs influence our wellbeing in many ways. They influence how we perceive the world and our actions, which then have consequences. Some actions are more reliable than others for increasing our wellbeing. Our beliefs dictate which actions we take to try and achieve our goals and they dictate which goals seem worth pursuing.

‘What produces human wellbeing?’ is an empirical question. That is, to answer that question we must experiment and observe what happens. It would be in our best interest to have our beliefs align with an accurate model of reality, including an accurate model of what reliably produces wellbeing. Reality always bats last, and bumping into reality can produce immense suffering, not only for ourselves but for others.

What are the helpful lessons an average person can take away from Street Epistemology?

Questioning is more effective than telling in order to help people reflect. Conversations about contentious and deeply-held beliefs don’t have to be argumentative. People are not their beliefs. It’s possible to persuade while maintaining a good relationship, or as we say, positive rapport.

What are the ways people can become involved with Street Epistemology?

The SE website is a great place to start. I highly recommend the SE Discord for a place to practice or get your questions about SE answered. The SE subreddit is nice for keeping up with new content that’s being created.

If you really want to get involved, SE has its own non-profit, Street Epistemology International. There are always big projects that are in need of volunteers and funding. We are currently in the development of a huge training course for SE. SEI can also help people fund their own SE projects.

Thanks so much for taking the time to answer these questions. If people want to sit down to chat with you, where can they find you?

In person, they can find me at Runyon Canyon in Los Angeles on most Sunday afternoons. Join the SE Los Angeles Meetup for more specific info. Or they can chat with me privately on Zoom by scheduling a time here.

Thanks so much, Erik, for the interview!